Introduction

As geopolitical risks and globalisation are reassessed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and war in Europe, we believe that Japan stands to benefit as more companies refocus on their home markets. Rising inflation could potentially break the cycle of disinflation and low wages, paving the way for the Bank of Japan (BOJ) to revise its accommodative policy. In addition to these macroeconomic factors, Japan’s emphasis on corporate governance reform could continue to help investors unlock value in 2023.

Geopolitical risk and Japanese companies

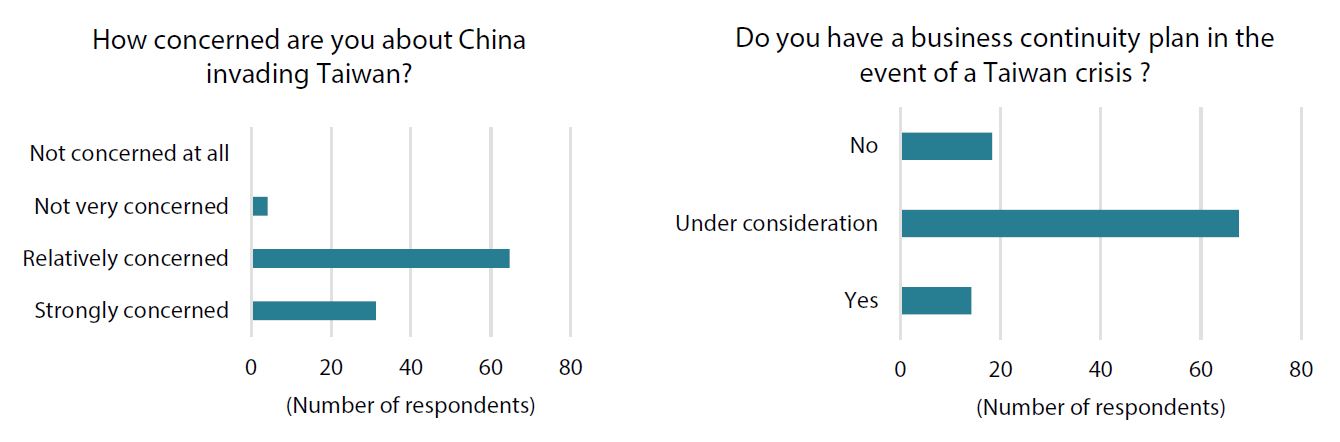

National and energy security became major focal points in 2022 in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The direct impact of the war is being felt most acutely in Europe, which has close economic ties with Russia. However, countries and companies not directly impacted by the war have also come to focus on geopolitical risk following the outbreak of the conflict. This is particularly evident in East Asia, where developments in the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula are now being watched even more closely (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Japanese companies with business continuity plans (Nikkei survey of 100 company CEOs)

Source: Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun as at 7 October 2022

Source: Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun as at 7 October 2022

It is unclear how much the global outbreak of COVID-19 has impacted politics at the national level. However, it is reasonable to assume that it made global companies more conscious of geopolitical risks after the pandemic disrupted supply chains and hampered global operations which had been built up over the past several decades. These developments have led many to ask: Has globalisation gone too far?

Rethinking globalisation

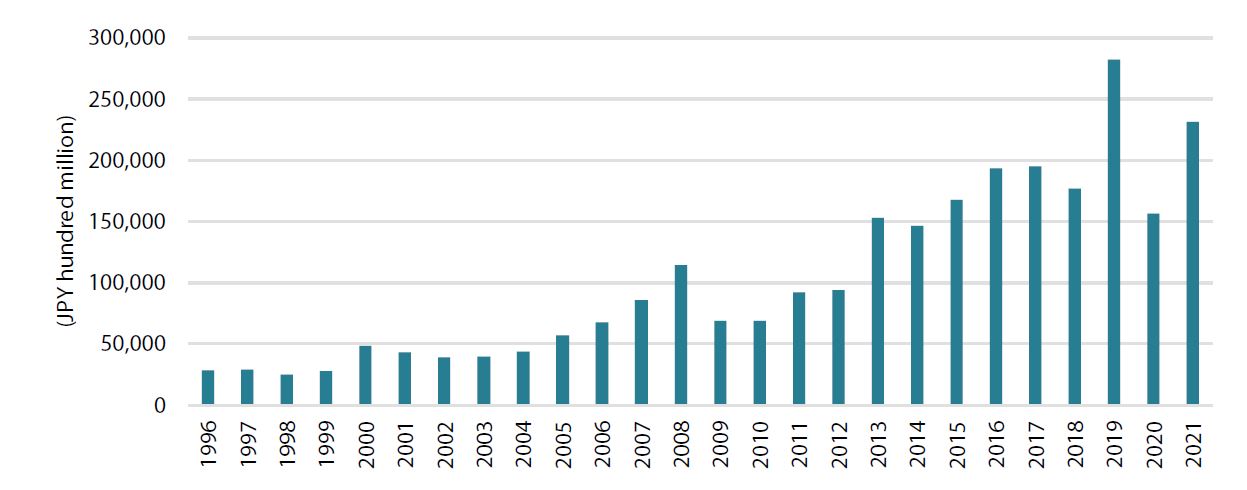

Globalisation has been one of the most dominant megatrends of the past several decades. Companies profited from comparative advantages brought about by globalisation, which resulted in increased international trade and higher efficiency in markets, leading to a wider availability of low-priced goods. Japanese companies have aggressively invested abroad in an effort to capture global growth and the trend had accelerated over the past ten years (Chart 2). Japan’s foreign direct investment amounted to Japanese yen (JPY) 28 trillion in 2019 (a year prior to the COVID-19 outbreak) quadrupling from 2009.

Chart 2: Japan’s foreign direct investments to other countries

Source: Ministry of Finance

Source: Ministry of Finance

Offshoring, or relocating, the production of goods to countries where they can be manufactured at a lower cost has been the key driver of globalisation. However, in light of the recent supply chain issues, we expect to see a shift in the other direction towards reshoring (bringing manufacturing back home), nearshoring (producing goods closer to home) and friend-shoring (deepening supply chains with trusted partners). Companies’ increasing focus on ESG and human rights due diligence is also expected to lead them to reorganise their supply chains and bring manufacturing/procurement closer to home.

While it is certainly not the end of globalisation, companies have started to optimize their supply chains given a new set of constraints that have emerged in recent years, most notably public health, geopolitical risks and ESG.

A study conducted by Waseda University professor Yasuyuki Todo estimates Japan will lose about 10% of GDP if 80% of imports from China is halted for just two months. Japanese automaker Honda, which currently generates over 30% of its sales in China, was reported to have launched a project to explore building out a supply chain which doesn’t use components made in China to manufacture automobiles and motorcycles. Meanwhile, Toyota is said to have demanded its suppliers to increase their semiconductor inventory level from three months to five months in order to shift its focus to “just in case” from “just in time”.

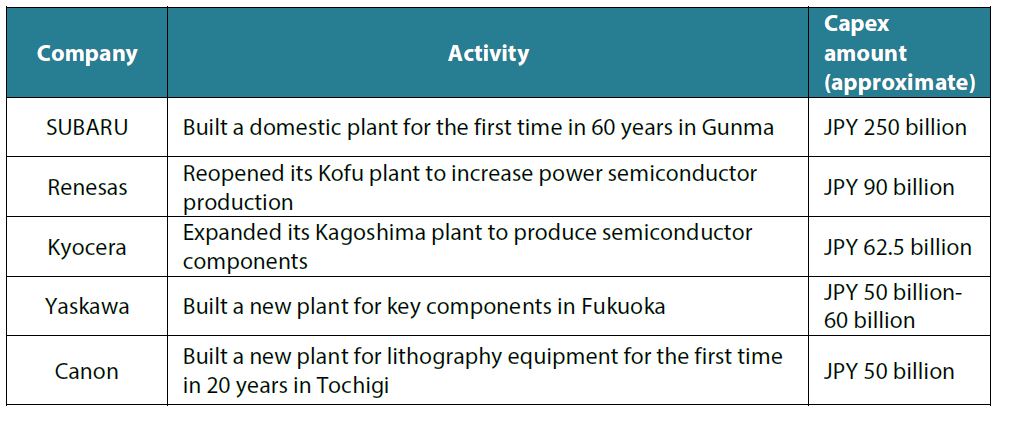

Several major Japanese companies made swift decisions to diversify manufacturing in 2022 and announced plans to invest more at home (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Japan’s manufacturing companies and capex

Source: Nikkei, 29 October 2022

Source: Nikkei, 29 October 2022

Reference to any particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security or to be relied upon as financial advice in any way.

The Japanese government is also supporting reshoring efforts, particularly in the technology space. In August 2022, a group of eight leading companies including Toyota, Sony Group and NEC set up a joint venture aiming to mass produce next-generation semiconductors to be used for supercomputers and artificial intelligence. This company, named Rapidus, was selected by the Japanese government in November 2022 to be subsidised (to the tune of JPY 70 billion) to ensure Japanese companies’ access to next-generation semiconductors and lessen their dependence on overseas suppliers. Rapidus plans to invest about JPY 5 trillion over the next 10 years. These developments follow TSMC’s plan to begin its first-ever manufacturing of semiconductors in Japan in 2021, the capital expenditure of which will be subsidized by the Japanese government. Companies such as semiconductor production equipment makers (SPEs) and material companies are also scrambling to build new factories at home not only to diversify their production but also to meet increasing domestic demand. The Nikkei reports that the trickle-down effect from the new TSMC new plant in the southern region of Kyushu is estimated to reach JPY 4.3 trillion over the next 10 years. We expect “made in Japan” to gain momentum more broadly in various manufacturing sectors in 2023.

Not all inflation is created equal

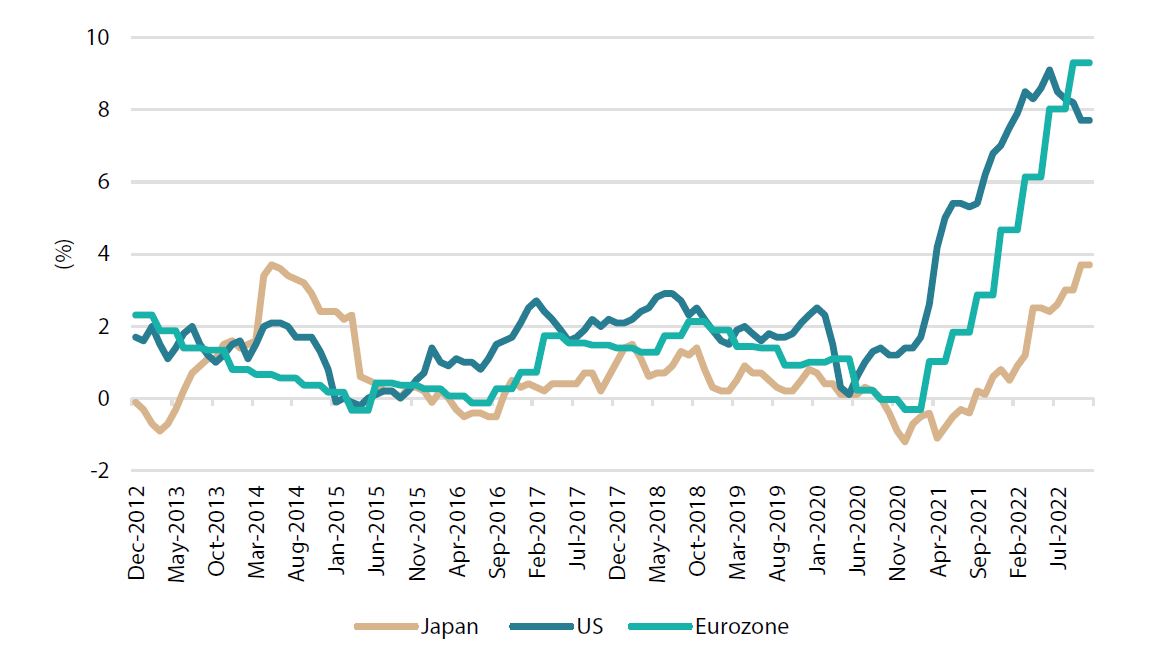

In terms of Japan’s macroeconomics, it will be increasingly important to monitor the cumulative effect of higher inflation in 2023. In the US and Europe, surging prices are considered an economic threat and their central banks are focused on deflating aggregate demand in an effort to combat decades-high inflation before it goes out of control.

On the other hand, for a country which suffered from the so-called “lost decade” following the bursting of the economic bubble in the early 1990s and a deflationary period in the early 2000s, inflation may not be entirely bad for Japan. This is because inflation has the potential to break the vicious cycle of disinflation and low wages, which is essentially a chicken-and-egg problem. It is widely believed that inflation by nature is driven by a self-fulfilling prophesy and, therefore, inflation expectations need to be raised for the actual inflation rate to move up. For inflation expectations to be positive (ideally close to 2%), there will have to be an exogenous shock that becomes a catalyst; the recent rise in import prices may therefore be what Japan needs.

We need to distinguish between certain items that are becoming more expensive due to higher commodity prices and those that are experiencing chronic deflation; that said, at an aggregate level, we are seeing Japan’s inflation rate pick up, with the latest data showing the October CPI rising 3.7% from the previous year (Chart 4) as of this writing.

Chart 4: CPI in Japan, US and Europe

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

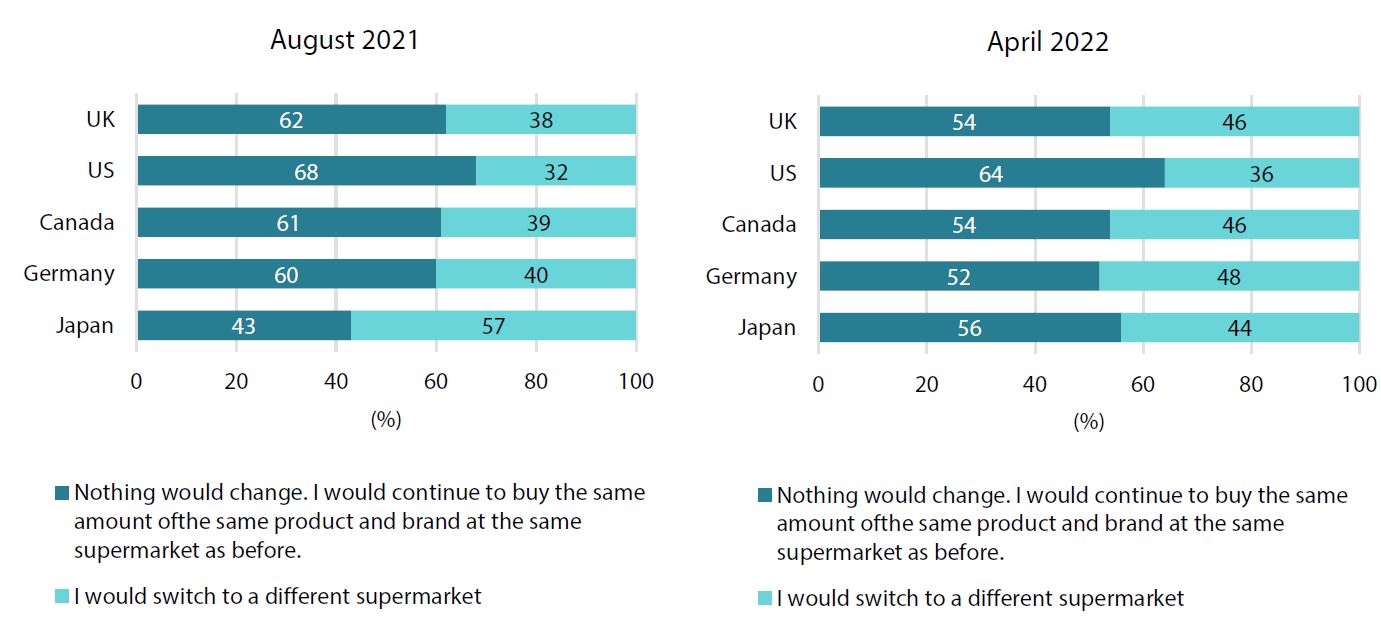

While Japan’s inflation rate is still low relative to that of the US and Europe, we are finally starting to see signs of inflation expectations rising in line with actual inflation. According to a survey conducted by University of Tokyo professor Tsutomu Watanabe, people appear to have become more resilient to an increase in the level of prices (Chart 5).

Reference to any particular security is purely for illustrative purpose only and does not constitute a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security or to be relied upon as financial advice in any way.

Chart 5: Change in inflation expectations

What would you do if the price of a product that you always buy at a supermarket rises 10%?

Source: University of Tokyo Household Survey, May 2022

Source: University of Tokyo Household Survey, May 2022

The second-round effect: Will a virtuous cycle finally begin?

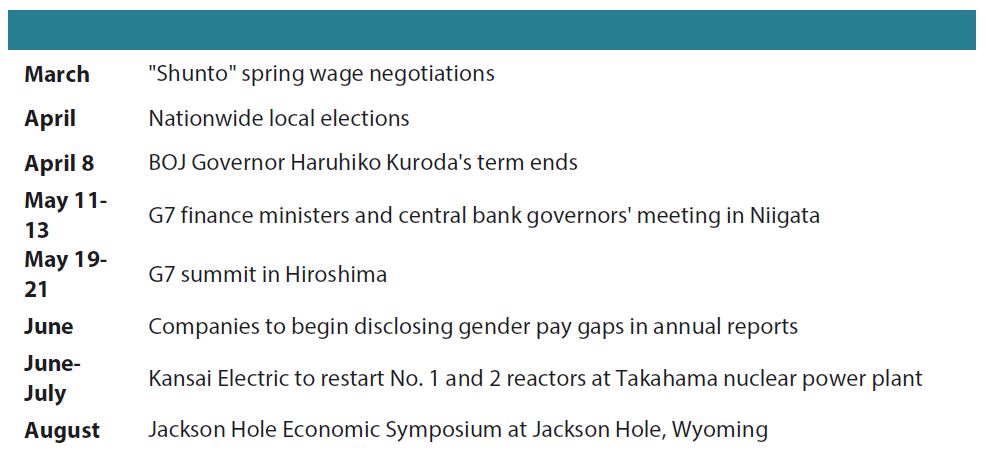

The “Shunto” or “spring wage offensive” is launched each spring in Japan, with company management teams and labour unions engaging in wage negotiations for the coming fiscal year starting in April.

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has called for higher wages in his “new form of capitalism” economic agenda and considers wage hikes to be critical in creating a virtuous cycle of growth and distribution. Labour unions are also becoming aggressive in calling for higher wages. Ahead of the coming negotiations, RENGO, the largest national trade union centre in Japan, is calling for a 5% wage hike, while the Japanese Federation of Textile, Chemical, Food, Commercial, Service and General Workers’ Unions (UA ZENSEN) is calling for a 6% hike.

Chart 6: Major market-related events in 2023

Corporate earnings have been solid thus far in fiscal year 2022 and the unprecedented level of buybacks (net purchase of JPY 4.5 trillion YTD through the week of 18 November 2022) implies that corporate managers consider the valuation of Japanese companies to be attractive. Japanese companies have accumulated a significant amount of cash and retained earnings over the years and there is increasing pressure on companies to raise wages now that inflation (as well as expected inflation) has finally started to rise. The Japan Business Federation (or “Keidanren”), the country’s biggest business lobby which boasts a membership of nearly 1,500 companies, is said to be encouraging its members to raise wages in 2023. Higher wages will clearly be positive for consumption thanks to households’ pent-up demand following the pandemic. A revival in inbound tourism should also contribute to Japan’s delayed recovery from COVID-19 (for a more detailed assessment please see Inbound tourism: An immediate boost for Japan released on 8 November 2022).

Reversal in yen weakness

Wage hikes could also pave the way for the BOJ to pivot from its current accommodative policy. After serving as BOJ governor for the past decade, current chief Haruhiko Kuroda’s term will end in April 2023, and his successor could be in a position to tweak monetary policy.

Meanwhile in the US, we expect the Federal Reserve to take a more balanced approach to managing its monetary policy and slow down the pace of its monetary tightening in the coming months. A resulting narrowing of US-Japan interest rate differentials will likely help the Japanese yen reverse its losses against the dollar in 2022.

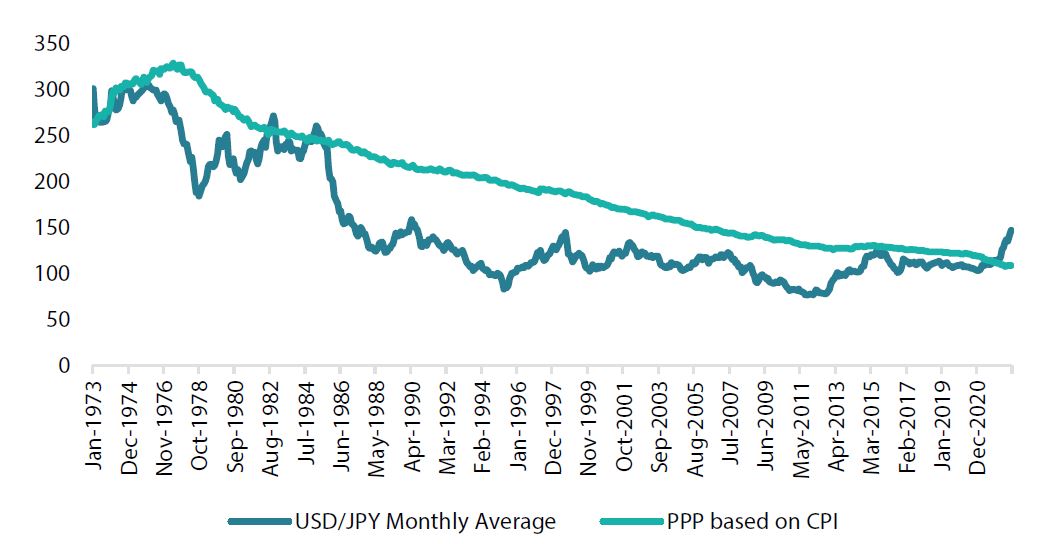

The yen has weakened very rapidly in 2022 and it is now trading below the PPP level for the first time in nearly 40 years. As such, the currency appears ready for a rebound.

Chart 7: Japanese yen vs. PPP

Source: Institute for International Monetary Affairs

Source: Institute for International Monetary Affairs

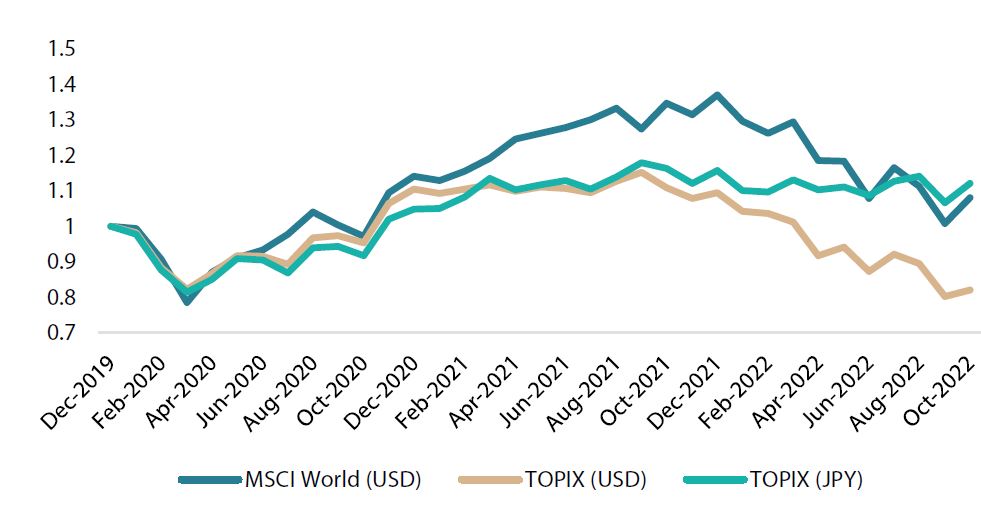

From an investment flow perspective, overseas investors have been net sellers with a cumulative outflow of JPY 2.5 trillion in 2022 (through the week of 18 November 2022). We think that rising expectations towards the yen reversing its losses will encourage overseas investors to return to the Japanese market to capture not only capital gains but also currency gains. We expect such flows to benefit the overall market.

Chart 8: TOPIX hedged and unhedged Returns vs. MSCI World

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

Corporate governance reform remains intact

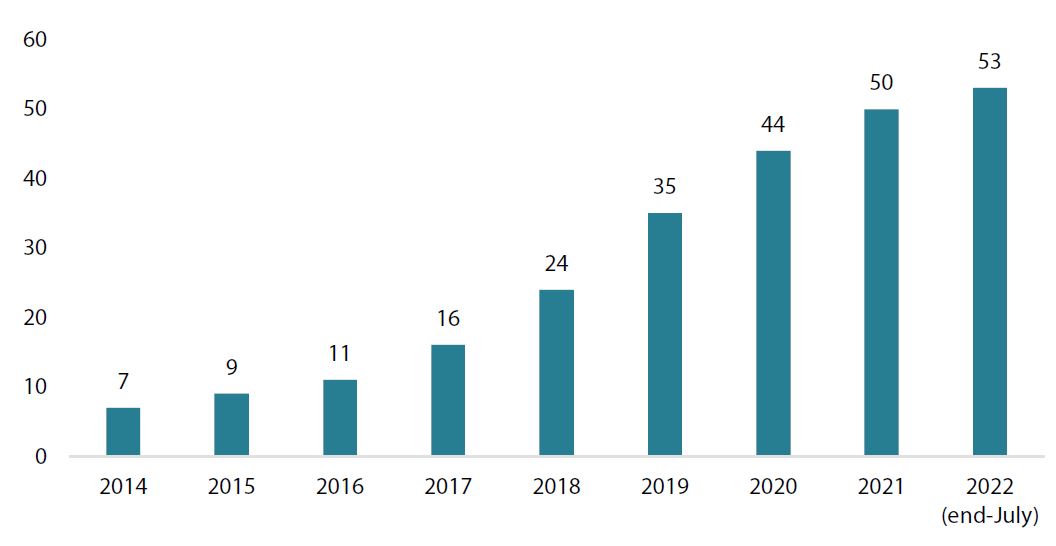

Finally, we believe that corporate governance will remain an important theme in 2023. Since Japan first introduced the Stewardship Code in 2014 and the Corporate Governance Code in 2015, the market environment has changed extensively. Companies have more independent directors, are focused on capital efficiency targets such as ROE and are engaged in share buybacks to benefit shareholders. The number of activist investors entering the Japanese market has also grown significantly. Companies are continuing to unwind cross-shareholdings while stricter proxy voting guidelines have resulted in traditional institutional shareholders applying more pressure for corporate reform. These developments make the market more attractive for activists as support from traditional shareholders is expected to help unlock value.

Chart 9: Number of shareholder activists in Japan

Source: IR Japan

Source: IR Japan

In September 2022, Prime Minister Kishida gave a speech at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and made it clear that corporate governance reform is an important policy which will be accelerated. Kishida mentioned establishing a forum to engage global investors on corporate governance issues.

We will accelerate and further strengthen corporate governance reforms in

Japan, such as establishing a forum in the near future to hear from investors

from around the world.

From a speech by Japanese Prime Minister Kishida at the NYSE on 22 September 2022 (Source: Prime Minister’s Office of Japan)

Following the prime minister’s speech at the NYSE, Japan’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) held talks with the Asian Corporate Governance Association and the International Corporate Governance Network. According to the FSA, it is scheduled to also hold a meeting with a group of US-based investors. We believe that future policies and guidelines will continue to reflect these discussions, which in turn are expected to help unlock and create shareholder value in 2023 and beyond.

Summary

Attempts by large Japanese companies to realign their supply chains and adapt to new global constraints could inject new life into “made in Japan” in 2023. Inflation, if accompanied by rising wages, could open a new chapter for a country which had suffered from a long period of disinflation and economic stagnation. Japan’s equities, in our view, are well placed to benefit from positive economic developments in 2023 as the environment surrounding the market has changed extensively amid ongoing corporate governance reform.